North Sea Oil: The Political Battle Over Britain’s Energy Future

With the party conference season now over, the future of the North Sea has emerged as a key dividing line in how the UK’s main parties approach energy, jobs, and climate.

A new Find Out Now poll (October 8) puts Reform UK in front at 32%, with Labour and the Conservatives tied on 17%, and the Greens rising to 15% — their strongest showing yet. The results underscore how energy, climate, and cost-of-living debates are shaping the political conversation, as voters respond to sharply different visions of the UK’s energy future.

Party Positions on the North Sea

Labour (in government) has pledged to end new oil and gas licences, focusing instead on renewables and investment in clean industries. Existing projects will continue, but no new fields will be approved. Labour argues this approach balances energy security with climate goals.

Conservatives propose to reverse Labour’s restrictions and “maximise extraction” from the North Sea, claiming this will strengthen energy independence and create jobs. Their platform includes reinstating export finance and trade promotion for UK oil and gas firms.

Reform UK goes further, calling for a full re-opening of drilling and exploration, promising to “unleash Britain’s energy” by cutting environmental regulations and restoring industry confidence.

Green Party opposes all new oil and gas extraction and calls for a rapid phase-out of existing production. The party argues that continuing to drill undermines the UK’s net-zero commitments and delays investment in renewables, energy efficiency, and green jobs.

North Sea Production and the Bigger Picture

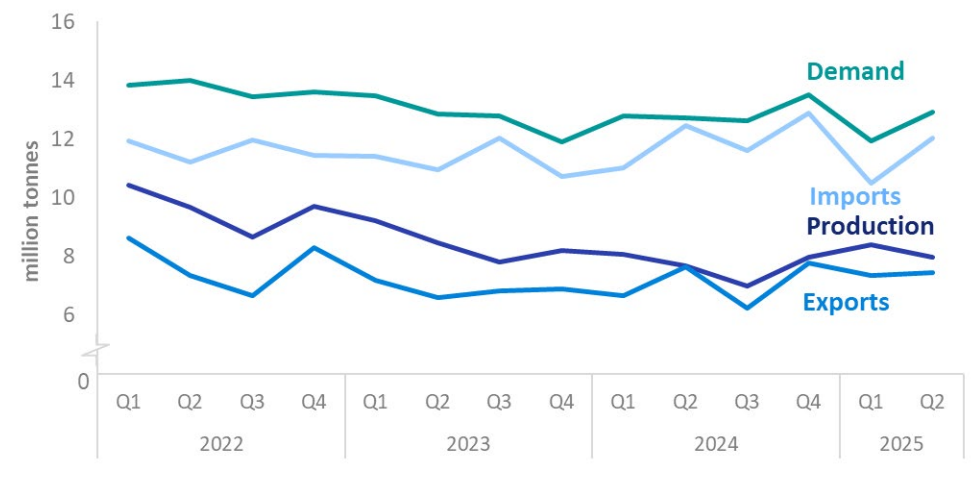

UK oil output has seen a brief uptick this year as maintenance schedules eased, but the broader trend remains firmly downward. Production from the North Sea has been declining for years as older fields mature and new developments become harder to justify economically. Regulators expect this gradual fall to continue through the decade.

While the North Sea is often invoked as a symbol of Britain’s energy independence, most of its oil doesn’t stay in the UK. Production is led by private multinationals such as Shell, BP, Harbour Energy, and TotalEnergies, which sell crude on global markets where prices are set internationally. That means higher output does little to lower domestic fuel bills — even though it’s often framed as a solution to energy costs.

The UK still imports more refined fuels than it exports, though refinery activity has risen slightly in 2025, helped by stable demand and fewer outages. Overall, the industry remains important for jobs and exports, but its role in directly supplying the UK’s own energy needs is limited.

Why the Debate Resonates

The North Sea has become a touchstone for wider political arguments about Britain’s economic future and energy direction. For some, it represents security and self-reliance, a way to sustain jobs in Scotland and the northeast while keeping domestic energy industries alive. For others, it’s a symbol of delay — a resource whose continued exploitation risks undermining net-zero targets and investment in clean technologies.

Voters are weighing up these competing visions: whether the future of British energy lies in maximising North Sea production or accelerating the transition to renewables. The real debate is about how long the UK should keep relying on oil and gas — and what balance between fossil fuels and clean power best serves national interests.